What appears from the trailers as a "heart-warming", charming film set in a Chinese kindergarten and fronted by a whole troupe of adorable, peach-cheeked kids paints actually a depressing picture of society.

Little Red Flowers by director Zhang Yuan is still showing at

The Picturehouse, and despite this grim introduction, I must say it is a film worth watching.

Warning: spoilers aheadGiven director

Zhang Yuan's previous films - the earlier

Mama,

Beijing Bastards,

East Palace West Palace - I should have expected

Little Red Flowers to be not just a straightforward narrative of a boy's mischief and how the odd man will always strike a deal of mutual respect and tolerance with his community. Because even if the odd man wants to, chances are the community will not.

Fang Qiangqiang, a 4 year-old, is sent to a boarding house kindergarten because his grandmother has returned to the countryside and his father, we gather from the brief shots of his workmen clothes, has other worries. There is no mention of a mother. Young Fang Qiangqiang is introduced to the factory-like environment of the kindergarten - the long straight rows of long tables in the dining room, the 2 long rows of concrete drains that serve as latrines, the uniform cots in the dormintory, and the giant building blocks in the indoor playroom are geared towards efficiency and uniformity of process and production. What more, once outdoors, you realise that the kindergarten is set in a complex not unlike the Forbidden City - old but previously grand and palatial chinese architecture with their stone balustrades, courtyards, lush gardens and miniature stone bridges (perhaps this is alluding to the phenomenon of "Children Palaces", a name given to kindergartens in a China that so loves its children). You learn through a few happy scenes of play amidst this complex of buildings and gardens that part of it is used by the military as a parade groud and another by a hospital.

The audience may notice these troubling images,

The audience may notice these troubling images, but our suspicions are at first distracted by 2 things. First, we may think that this being a Chinese film, such seemingly surreal juxtapositions and suggestions of oppression could just be part of life in China. Second, the cinematograhy and art direction cleverly disguises these settings and images with nostalgic pinks, baby blues, beige and the occasional reds. The film is nothing if not beautifully shot and composed, with colours and images belonging to a 50s children's book. In the same way, even if the Head Teacher Li may seem a tad controlling, she gamely plays with the children and her teachings are always about personal hygience and independent living - lessons which most parents will not doubt the "usefulness" and "correctness" of. There is even a pretty, kind and generous younger teacher to give the audience hope. As such, we may be tempted not to romanticise too much Fang Qiangqiang's rebelliousness.

But by the middle of the film, you must be terribly blind not to know that the kindergarten is but a guise for the larger systems of society. At first, individual agency is first to be cajoled and bought with the promise of "little red flowers" (paper flowers stuck handed out to the child, and correspondingly stuck against the child's name on a board) - a reward for the obedient child who performs as instructed. Fang Qiangqiang, despite his rebellious streak, is not immune to this reward system. When his little pigtail is cut off by the head teacher because it risks harboring lice (an ironic reference perhaps to the cutting of pigtails during China's supposed escape from Manchurian monarchic rule into a modern, democratic republic), he is denied his little red flower because Head Teacher Li believes more in negative motivations than positive encouragement. Perhaps hoping to break his rebellious spirit (all 4 short years worth of it!), Head Teacher Li continues to ignore Fang Qiangqiang's attempts to conform.

And because Fang Qiangqing does not receive his rewards soon enough, he learns instead to find the loopholes in the rules and to make the best of his disobedience and resultant punishments. For a while, he finds friendship in a pair of sisters, but 2 is stronger than 1, and they too, turn against him when his mischief gets them into trouble. (The scene where they play doctor is really funny, but in retrospect, this metaphor of illness - real or pretend - is discomforting)

As the film progresses, Fang Qiangqiang grows more and more anarchic

As the film progresses, Fang Qiangqiang grows more and more anarchic (well, as anarchic as a 4 year old in a kindergarten can be) and more and more lonely. But he does not realise this. The poor boy even hallucinates! At first he finds power in sharing his suspicions that Head Teacher Li is a child-eating monster to the other children and seeds a semi-revolution to "catch the monster" one night. When his role in this disturbance goes undetected, his belief in his own disruptive power grows and he starts being a bully. Finally, when his rebellion culminates in his swearing at a teacher, he is subjected to solitary confinement. Unconvinced that all this is punishment enought, this is followed by a period of isolation among peers who are instructed to ignore him.

Throughout all this, the audience roots for the adorably rebellious Fang Qiangqiang. We associate with him because he is the very picture of the boy who tells the naked Emperor he is naked. It is an honesty that is both rebellious and innocent. When a girl sings a song about apples as taught by the teacher, Fang Qiangqiang deliberately reverses the lyrics to sing "The big apple I keep for myself, the small apple I give to my friend." At night, he himself runs out into the snow-lined playground naked and plays with his shadow, whispering - "Who are you? Can you please don't follow me?"

As such, right to the end of the film, we want his peers and teachers to recognise his creative independence. But we are inadvertantly wanting to see him surviving untouched in the highly regimented world. Zhang Yuan tells us that ours is but wishful thinking. Something must give.

At the abrupt end of the film (abrupt because we are nowhere near what we hope to see), we are left with the image of an 4 year-old who has strayed from his group and is perhaps lost. What we see is that he is so exhaused he cannot even respond when his name is called. And more than exhaustion, perhaps it is because he does not want to be found, perhaps it is an insistence on being apart... or perhaps it is because he no longer recognises his name.

>>

Indiewire Interview with Zhang Yuan========

p/s Elsewhere on the blogosphere,

forty calibernap sings the song of the creative individual in his loved-hated city.

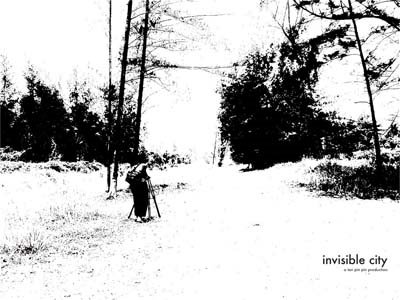

J and I finally heard Mr Yew Hong Chow play the harmonica live this at the DVD launch of Tan Pin Pin's Singapore Gaga this evening in Substation's Timbre cafe. A small man who with his hands over his mouth, the harmonica invisible from where we sat, made sounds I've previously thought came from other instruments. Yet he amazed us with his humility. When called on stage to be thanked, Mr Yew thanked the director instead - for raising interest in the harmonica. (Mr Yew's CD will be released next week.)

J and I finally heard Mr Yew Hong Chow play the harmonica live this at the DVD launch of Tan Pin Pin's Singapore Gaga this evening in Substation's Timbre cafe. A small man who with his hands over his mouth, the harmonica invisible from where we sat, made sounds I've previously thought came from other instruments. Yet he amazed us with his humility. When called on stage to be thanked, Mr Yew thanked the director instead - for raising interest in the harmonica. (Mr Yew's CD will be released next week.) Despite there being a stage, mics, a host, a reception table and a gift for guests (an old skool condensed milk tin used for takeaway kopi), the event was great for feeling more like a family reunion party of sorts than a DVD launch.

Despite there being a stage, mics, a host, a reception table and a gift for guests (an old skool condensed milk tin used for takeaway kopi), the event was great for feeling more like a family reunion party of sorts than a DVD launch.  What remains for me to say now at 2am is this: Go buy The DVD, available now at Kinokuniya bookstore, Objectifs, and Earshot at the Arts House/Old Parliament.

What remains for me to say now at 2am is this: Go buy The DVD, available now at Kinokuniya bookstore, Objectifs, and Earshot at the Arts House/Old Parliament.