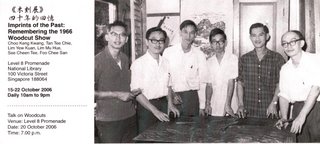

Curated by a good friend CT and art researcher Koh Nguang How (Koh was behind Errata), this exhibition resurrects a 1966 exhibition by 6 woodcut artists first held at the old Stamford Road National Library.

Curated by a good friend CT and art researcher Koh Nguang How (Koh was behind Errata), this exhibition resurrects a 1966 exhibition by 6 woodcut artists first held at the old Stamford Road National Library. Of course, the old National Library is now a vehicular tunnel. But 40 years ago, this post-independence exhibition was held at a site symbolic of Singapore's post-independence future, a public institution of learning built withboth government funds and donations. The 1966 exhibition was a decided writing of art history. 6 artists presenting art grounded in the realities of Singapore in their time, its streetscapes, its trades, its people. A fresh page of art history.

Today, of the 6 artists - Lim Mu Hue, Tan Tee Chie, Foo Chee San, Choo Keng Kwang, Lim Yew Kuan, See Cheen Tee - 5 are alive. Most are in their 70s or 80s. It is an exhibition to remember and preserve. And remembering is certainly as important as learning for the future.

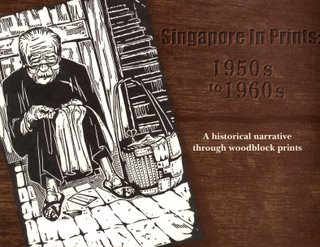

The woodcut had been an important art because it was the art of the vernacular. It was relatively inexpensive, compared to oils. Its art was reproducible, allowing everyman to possess one. And perhaps owing to the starkness of dark versus light, expressions of a people's daily suffering were particularly dramatic. Gaunt faces were more so. Dirty streets and hovels more dilapidated because of the harshness of the lines. It was a democratic art, used in magazines and the illustrations of essays and books. In fact, its prints could be produced without a mechanical printing press, but anywhere - in homes.

The woodcut had been an important art because it was the art of the vernacular. It was relatively inexpensive, compared to oils. Its art was reproducible, allowing everyman to possess one. And perhaps owing to the starkness of dark versus light, expressions of a people's daily suffering were particularly dramatic. Gaunt faces were more so. Dirty streets and hovels more dilapidated because of the harshness of the lines. It was a democratic art, used in magazines and the illustrations of essays and books. In fact, its prints could be produced without a mechanical printing press, but anywhere - in homes. And for all these reasons, it was convenient as an revolutionary art, an art of protest. In modern history, if printing presses were legally governed and regulated as potential sources of incendiary information, then the woodcut allowed the artist, the revolutionary, the student, the publisher etc to circumvent inspection and produce quantities of an underground pamphlet or poster. For example, Lu Xun's woodcut movement was as instrumental as his writingin in forging a new ideological art.

We met Koh at the exhibition today and besides his many stories about the artists and their works, I asked him briefly about the relevance of woodcut today. I said that with print-making being institutionalised in art colleges, it has lost some of its immedicacy. Today, it is either one of the art forms more closely aligned with craft and design, or elevated to some exclusive side-dish for the more established artist. Koh agreed that with the internet and the computer printer, there was really no issue of disseminating information anymore. But he said that even today, in countries like Thailand and Indonesia, the woodblock/print strangely retained its relevance during periods of protest.

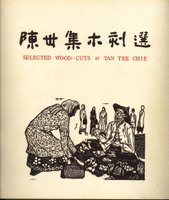

For me, every time I meet Koh, I learn something new. I remember the first time I met Koh was with CT at another woodblock exhibition at the then Singapore History Museum (now National Museum) in the late 90s. The image above is from the exhibition brochure. Then, both CT and Koh told me many more stories behind the prints and their blocks, especially those pre-independence prints. Later, wandering around the dusty bookshops of Bras Basah Complex, I found 1 last copy of fellow-Hainanese Tan Tee Chie's 1975 book with a limited run of 1000 that CT had recommended. Its preface was by Tham Hean Chow (haha, perhaps, he too came from the same Hainan village as my grandfather) and the English text was edited by Georgette Chen. I have sat it fondly on my shelf of favourite art books.

For me, every time I meet Koh, I learn something new. I remember the first time I met Koh was with CT at another woodblock exhibition at the then Singapore History Museum (now National Museum) in the late 90s. The image above is from the exhibition brochure. Then, both CT and Koh told me many more stories behind the prints and their blocks, especially those pre-independence prints. Later, wandering around the dusty bookshops of Bras Basah Complex, I found 1 last copy of fellow-Hainanese Tan Tee Chie's 1975 book with a limited run of 1000 that CT had recommended. Its preface was by Tham Hean Chow (haha, perhaps, he too came from the same Hainan village as my grandfather) and the English text was edited by Georgette Chen. I have sat it fondly on my shelf of favourite art books.My friends, ampulets present here our own toast to the woodcut - its past, present and future!

we dare you, raffles! - er, actually it's a lino print made at night class

No comments:

Post a Comment