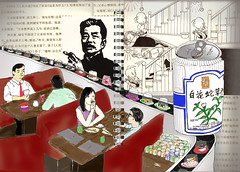

This fizzy oldenlandia drink from China is the "Chinese Perrier" - click for larger view

I remember the one time I've been to China. It was in 1996 and 2 friends and I decided that it would be fun to spend our summer vacation being a volunteer on the Doulos.

The Doulos is basically a giant floating, non-profit bookstore that sails around the Asia-Pacific. Once on board, one of my friends got assigned to the book warehouse, another as a deckhand (er, it's more like "housekeeping" since toilet cleaning usually took up her whole morning), and I had the pretty cushy job in the pantry section. That meant I helped with serving the 5 meals daily and cleaned up the canteen, together with a group of women mostly from Korea, Philippines, Denmark and the UK.

The ship docked at Shanghai after 3 days or so of bad-weather sailing from the Philippines.

The ship docked at Shanghai after 3 days or so of bad-weather sailing from the Philippines. And I remember watching the scene from the pantry windows as the ship entered the Shanghai harbour and thinking to myself, wow, what a way to arrive in Shanghai! Right by the Shanghai Tang! (cue music from the 80s Hongkong TV drama series)

Since then, I've not felt the urge to visit China and I don't think J and I will anytime soon. J's folks brought him to see their relatives in some village...and if you know J, you can imagine how torturous that trip must have been for Mr. No-dirty-toilets-please!

But I admit, having just started to read Zhang Yi He's (章诒和) book of memories 往事并不如烟, there's just a bit more curiosity now about that complex hulk of a nation.

Zhang Yi He is a researcher at the Chinese Institute of the Arts, and daughter of intellectual Zhang Bo Jun who was disgraced in a 1957 communist witchhunt for rightist elements. Dedicated to her father, her book recollects 6 figures from that tumultous period for intellectuals in modern Chinese history.

Zhang Yi He is a researcher at the Chinese Institute of the Arts, and daughter of intellectual Zhang Bo Jun who was disgraced in a 1957 communist witchhunt for rightist elements. Dedicated to her father, her book recollects 6 figures from that tumultous period for intellectuals in modern Chinese history. How to resist a book with such a poetic, defiant title? The phrase/idiom 往事如烟 literally means "the past is like smoke". But the title insists that this is not true (并不 = "in fact, it is not"). And on what basis does Zhang Yi He lay her charge against the accepted wisdom of that phrase? Nothing. Nothing, but the singular insistence that a person's memories, re-told, is enough to bear the weight of an accepted wisdom. And in many ways,the characters and drama in this book live out this poetry - their individual lives, drawn against the thick curtains of history.

Shi Liang in the 50s

Shi Liang in the 50sThe most moving chapter has as its central figure Shi Liang (1900-1985), the first minister of justice of the people's republic, and a leading figure in the Chinese women's movement. Shi Liang is a family friend, and Zhang Yi He recounts her childhood memories of Shi Liang with great admiration.

But we soon learnt that Shi Liang was also the one who had "betrayed" her father Zhang Bo Jun in the 1957 purging of rightist intellectuals. Strangely, Zhang appears to place little of blame on her. Perhaps it is because Zhang understands too well that no one, not even the admirable Shi Liang, was exempt from the pressures and forces of history and ideology in those years leading to the cultural revolution. In fact, years after the 1957 incident, Shi Liang was herself hauled up and humuliated by the Red Guards.

Zhang Bo Jun was in the crowd that day, specifically instructed by the red guards to attend. I guess because who watches you as you are being "corrected" by the red guards is part of the correction (aka punishment) itself. Shi Liang was called because her old love letters to a condemned rightist #1 Luo Sheng Ji was found among Luo's possessions. Old and ill with high blood pressure, the red guards made Shi Liang bend low as she was questioned. When finally asked on her relationship with Luo, she merely replied "I love him". Considering the times, she was one brave radical woman!

That one's love letters should outlive the object of one's love, and be dragged into the public realm of politics and ideology attests only to 1 thing - that the personal (relationships, memories) outlives and persists the twists and turns of history. Years after, on a visit to the elderly stateswoman Shi Liang, Zhang Yi He witnessed her break down in tears at the casual mention of her husband's passing and concludes:

是的,脆 弱的生命随时可以消失,一切都可能转瞬间即空,归于破灭,惟有死者的灵魂和生者的情感是永远的存在。

bad, literal trans: yes, our weak lives may disappear any moment, everything can in a blink of an eye become nothing, given over to destruction, but the spirit of the dead and the feelings/emotions/sentiment of the living alone persist.

I am sure the China today where our more enterprising fellow-islanders are flocking to get a spoonful of that lucrative market is no more the China in Zhang Yi He's book. Times have changed. In most countries, the time for intellectuals has passed now that all the ideological battles have been fought, won, discounted and dis-armed. And maybe with the fiercely capitalist (or should I just call it avaricious) reality, 情感 may not even matter any more.

This is why we also, like Zhang Yi He, must remember and tell stories of what needs to be remembered. Then the past will not, in fact, be like smoke.

No comments:

Post a Comment