Monmow Disease is like a X-man type mutation disease - but unlike Wolverine or his Marvel colleague Spider Man - those who start mutating into dog-like figures don't naturally assume super powers, they die. It starts with bad headaches, a taste for raw meat before bone structures shift. The face protrudes in a snout and finally the spine curves.

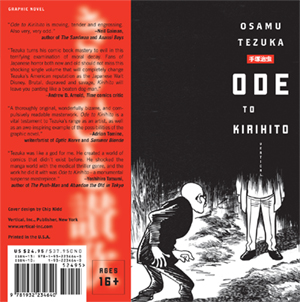

Thank goodness Monmow disease is but an invention of Osamu Tezuka, he who created less horrifying things like AstroBoy, Kimba the white lion (ah, I remember watching the cartoons) and Phoenix. But Ode to Kirihito, with its crippling disease, is my favourite Tezuka work. Originally serialised in Japanese between 1970-71, it has just been translated and published by Vertical with a fantastic book design by Chip Kidd.

I'm finding it hard to not say too much about the narrative, lest I spoil your experience of being seized, frama by frame, all 822 pages of Ode to Kirihito. But it will seize and fascinate you. At times suspenseful and at times melodramatic, there are also these dark and perverse, yet strangely comic moments... such as a nympho human-tempura. Yup. No kidding.

I'm finding it hard to not say too much about the narrative, lest I spoil your experience of being seized, frama by frame, all 822 pages of Ode to Kirihito. But it will seize and fascinate you. At times suspenseful and at times melodramatic, there are also these dark and perverse, yet strangely comic moments... such as a nympho human-tempura. Yup. No kidding. But the creator of Astroboy is ultimately driven by a sense of humanity's fallenness - corruption, greed, selfishness, despair and bigotry. These are the diseases, not the Monmow, that make us more beast than man. But because this moral degeneration is more conveniently hidden behind power and the powerful's cowardice, we are fearful when physical manifestations of our fallenness in our bodies or community and society emerge instead. And it is this our response to the latter - i.e. disease, poverty, violence - that reveals our moral cowardice, be it a response of fear or of deliberate ignorance.

3 years ago during my first trip to Tokyo, I spent a day with a youth volunteer organisation. Together with a busload of Japanese teenagers and twenty-somethings (see pic right), we drove out to the suburbs to visit a centre for folks with intellectual disabilities. One of the volunteers (I forget his name now) described to me what he felt was particular to Japan, the sense of shame and a desire to hide away relatives who had disabilities of any kind. He said until recently, parents would hide their kids at home if they were disabled or shipped them off to a home usually located in some quiet, remote place.

3 years ago during my first trip to Tokyo, I spent a day with a youth volunteer organisation. Together with a busload of Japanese teenagers and twenty-somethings (see pic right), we drove out to the suburbs to visit a centre for folks with intellectual disabilities. One of the volunteers (I forget his name now) described to me what he felt was particular to Japan, the sense of shame and a desire to hide away relatives who had disabilities of any kind. He said until recently, parents would hide their kids at home if they were disabled or shipped them off to a home usually located in some quiet, remote place. I was reminded recently on a few occasions that special needs schools in Singapore do not come under the purview of the Education Ministry, but are pretty much left to volunteer organisations to manage. While education regulations in Singapore provides for compulsory primary education up to the age of 12 for all Singaporean kids, it seemed that this did not apply to kids who were not eligible for mainstream primary schools. In the same way I think the Education Act, which stipulates the proper training and qualification of principals and teachers to mainstream school, does not extend the same provisions to special needs schools. (A forum letter last week to the ST raised this again) For too long our transport companies have also gotten away with not providing wheelchair access to our train stations and buses. More than 10 years of petitioning later, our train stations and buses are now slowly being revamped for universal accessibility.

Of course, none of this compares to the extreme depictions of injustice, bigotry and prejudice in Tezuka's Ode to Kirihito. But perhaps art and fiction hold up timely mirrors, even if or especially because they distort the figures and faces we have grown so used to seeing - and believing.

No comments:

Post a Comment