image by J

Paradise is an island. So is hell. (p6)I remember having a world map pinned on the wall of my bedroom when I was growing up. But that was before my father brought home a beach ball-sized model globe. It was a relief model, where if you ran your finger across the surface, you could "read" the mountain ridges.

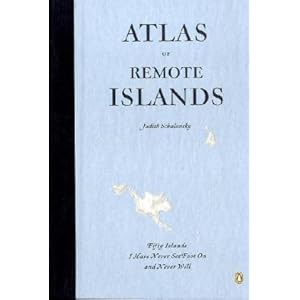

In the preface of Judith Schalansky's Atlas of Remote Islands: Fifty islands I have never set foot on and never will, she describes a similar experience of maps, atlases and globes.

While I confess it was the cover of this beautiful book (Schalansky trained as a graphic designer, and had designed the book and laid out the text) that first drew me, it was a brief read of the preface that convinced me to take it home from the bookstore. In the preface, Schalansky teases out man's fascination with the far frontier, our desire to conquer via knowledge and documentation, and the story threads behind these abandoned, conquered, disputed, cursed, marginal slivers and dots in the vast oceans.

While I confess it was the cover of this beautiful book (Schalansky trained as a graphic designer, and had designed the book and laid out the text) that first drew me, it was a brief read of the preface that convinced me to take it home from the bookstore. In the preface, Schalansky teases out man's fascination with the far frontier, our desire to conquer via knowledge and documentation, and the story threads behind these abandoned, conquered, disputed, cursed, marginal slivers and dots in the vast oceans. An island offers a stage: everything that happens on it is practically forced to turn into a story, into a chamber piece in the middle of nowhere, into the stuff of literature.(p20)

For each of the 50 islands covered, Schalansky reproduces a drawing of the island on a scale of 1:125000, and offers a write-up crafted from facts and stories culled from histories, travellers' reports and other accounts - fictionalised fact, fact as fiction.

For each of the 50 islands covered, Schalansky reproduces a drawing of the island on a scale of 1:125000, and offers a write-up crafted from facts and stories culled from histories, travellers' reports and other accounts - fictionalised fact, fact as fiction.For me, the names of these islands alone are enough to fire the imagination.

Imagine: Possession Island, Deception Island or the first entry in the book Lonely Island. The names of places on these craggy, icy or just plain uninhabitable places tell equally of their painful realities. Try spending the night at Misery Fjellet or the Comfortless Cove! Even those islands with less unfortunate names promise some kind of an adventurer's tale (Raoul Island, Tristan da Cunha, or the fictionalised Robinson Crusoe Island) or folklore as exotic as the sounds of Banaba, Takuu or Tikopia.

Peaceful living is the exception rather than the rule on a small piece of land..."(p19)I guess islands will always fascinate us, just as cities do. Both provide the circumscribed conditions of laboratories, prisons and retreats. The former bound by physical nature, the latter by human nature.

Schalansky's own story illustrates the boundaries of a city being drawn, redrawn and erased. Born in East Germany, when travel out of the country was not possible, Schalansky's early fascination with maps was somewhat ironic. Yet when the Berlin wall fell and she was free to travel out of t=her country, the country itself "disappeared from the map". It seems apt that she now resides in Berlin, in this renegotiated city.

Of course, it is also hard not to think about our own (in comparison) less remote and larger island when reading this book. Like many of these remote islands, our island can speak also of a colonial past, mythic and fictionalised creatures, (to many still) authoritarian powers and the utopian dream, or islandwide scientific/sociological experiments.

But unlike these islands, geography has undoubtedly given us a kinder fate.

No comments:

Post a Comment